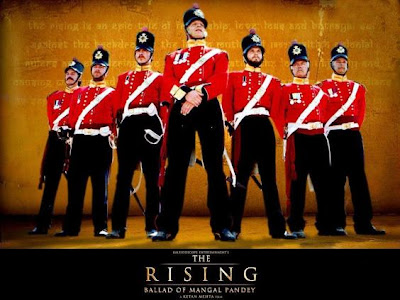

“Awesome” is the one word that comes to mind when I think of Mangal Pandey: The Rising. At least for a Bollywood film. And although my Bollywood movie watching experience is limited, I find that rich stories are often ruined by the use of redundant song and dance, poor editing, and/or a lack of realism. Yes, I understand that I may be culturally deprived, I am plagued with western ignorance, and I don’t understand the significance of several key scenes; however, I judge movies based on what I take away from them. Mangal Pandey: The Rising is an exception to my dislike of Bollywood movies. The movie is a good epic, not historically accurate, but it was realistically able to portray the uprising of the Indian people against the corrupt and tyrannous East Indian Company.

Bollywood superstar, Aamir Khan returned to big screen after a four-year hiatus to play Mangal Pandey. This was a perfect casting for a Bollywood production, because only a high profile personage such as Khan could play the life of one of the nation’s greatest legends. The movie revolves around the relationship between Pandey and his superior officer and close friend Captain William Gordon (portrayed by Toby Stephens). Throughout the course of the movie, the two men follow a bumpy yet similar path. The story begins with Captain Gordon’s flashback to a battle during the Afghan war in which Gordon was gravely wounded by enemy forces. While under heavy fire, Panday drags Gordon to safety thus saving his life. In return, Gordon gives Panday his pistol and a bond of mutual respect is formed between the two men. For Gordon, Panday is a loyal subordinate who leads the other sepoys, and for Panday, Gordon is a trustworthy leader who will protect the best interests of his men.

For the first hour of the movie, Pandey was loyal sepoy of the company, and at one point, he fired onto his own people; however, the turning point of the movie shortly follows the scene in which Pandey is the first sepoy to bite the head off of one of the cartridges rumored to be tainted with cow and pig fat. Gordon was the one who unknowingly assured Pandey that the rumors were false. As Pandey was walking through the village one day, the cross-eyed untouchable, Nainsukh, bumped into him. Pandey being a Brahmin (higher caste), began to scold Nainsukh, but he was quickly silenced by Nainsukh’s mockery in which he said “who better than you, now that we’re both the same…untouchables.” Nainsukh was able to prove to Pandey that the rumors were true by showing him the cartridge factory. Pandey was devastated and his greatest concern was the fact that he would lose his high caste status and become an untouchable (Majumdar, 1773). Pandey immediately goes to Gordon’s home to return the pistol, and denounce their friendship. It is from the point on that Pandey begins his rebellion towards the Company.

Parallel to Pandey’s transition from loyal sepoy to Indian freedom fighter, we see Gordon follow a similar transition. At first, Gordon is a close friend of Pandey and sympathetic to the natives, but he maintains his Company identity. He is submissive to the brutality of the company and fellow officers, and he follows orders without questioning. We first see Gordon question his loyalty at a Company dinner party in which he condemns the immoral and corrupt practice of the Company’s opium trade. We see his compliance to the Company quickly deteriorate after he falls in love with Jwala (portrayed by Ameesha Patal), the women he saved from a Sati ceremony, as well as discovering the truth about the the musket cartridges.

Pandey and Gordon face off in a short battle after Pandey leads a small attack on the Company troops. Pandey defeats Gordon, but he spares him his life. Pandey then goes on to single handily fight the troops, and attempts to sacrifice himself just before capture. The suicide attempt was failure, and we next see Pandey in the hospital with Gordon by his side. Gordon tells Pandey that his only chance is to plead guilty, apologize, and he warns him of a terrible bloodshed if he does not. Pandey’s final words to Gordon were, “India is rising and nobody can stop it, not even my life.” Gordon gave the court the same argument about bloodshed that he gave Pandey, and that their actions are leading to their own downfall. The court did not listen to Gordon’s plea and sentenced Peday to death. Just before Pandey is hung, he yells “Halla Bol” (attack). As Pandey’s body is dangling in the air, the spectators take a few moments of silence, and then Nainsukh (the untouchable) leads a charge against the Company while screaming “Halla Bol”. During the final scene of the movie, the narrator explains that the British Crown took over the governance of India, and that Mangel Pandey inspired the nation to fight for freedom, and at the same time footage of the Gandhian movement was being shown

Going back to the beginning of the movie, the first shot we see is of a painting that transitions into actual sunrise over the Ganges River. This scene then shifts to an elephant with its trunk lowered. It then raises it into their air while sounding its trumpet. This scene is a quick glance of the entire movie. Like the lowered trunk of the elephant, we first see Pandey being escorted to the gallows with his head down. At the end of the movie, just before the hanging, we see him being escorted to the gallows again, but his head is held high (raised tusk). Like the elephant sounding it’s trumpet, Pandey yells “Halla Bol” just before his execution. The sunrise, the raising of the elephant’s trunk, and Pandey all symbolize rising up in order to reach a new life.

A common trait of Bollywood films is to associate characters with beloved deities. In

Pyassa, Vijay is an embodiment of Christ, and Birju is an embodiment of Krishna in

Mother India. Based on my knowledge of Hinduism, I was unable to associate Pandey with any diety. Possibly, I could relate him to Shiva or Kali because he attempts to destroy the evil Company out of love and compassion for India. The East Indian Company is related to Ravana in the movie. Ravana was a demon king who kidnapped Rama’s wife in the Indian epic

Ramayana. In the scene in which Pandey is confused about the existence/purpose of the Company, Gordon explains to him that a company is created to make a profit. Gordon’s notices that Pandey is still confused, so he compares the company to Ravana. He explains that the Company has thousands of head to Ravana’s ten heads, and they are all glued together by greed.

Mangal Pandey: The Rising received a lot of criticism and controversy, mostly because of its historical inaccuracy. The movie almost gives full credit to Mangel Pandey for starting the revolution against the East Indian Company in the name of freedom; however, according to Majumdar and Chakrabarty, the real life Pandey never spoke a single word about “our freedom”(Majumdar, 1774). They also suggest that the British created the Mangal Pandey myth (Majumdar, 1175). There is historical documentation about a man named Mungul Pandey of the 34th Regiment who rushed onto a parade-ground shouting, “Com out, men! Come out, men! You have sent me out, why don’t you follow me? You will have to bight the cartridges! Come Out for your religion;” however, this about the extent of his efforts and notice that freedom was not mentioned (Ball, 45).

Historical accuracy for a movie is unnecessary because movies are meant for entertainment. Alfred Hitchcock best summarized the separation between filmmaking and historical accuracy by saying, “it is not the responsibility, nor interest, of an artist to document historical reality” (History written with lightening, 52). There is an opening quote of the movie that states, “where history meets proud folklore, there legends are born.” This is proof that the movie was not an attempt to distort history, but it was meant to tell the story of the Indian nation coming together to fight for it’s sovereignty and freedom. Mangal Panday was used a symbol for the cause as a whole

As I mentioned before, I feel that potentially great stories in Bollywood movies are often ruined because of all of the Bollywood elements. I thought

Mangal Pandey: The Rising was a decent story, but a great movie. It is the most westernized Bollywood film I have seen, and I have no doubt that is why I enjoyed it, but like I said, I judge movies on how feel about them, not on what I am supposed to feel about them. I even felt the music element was appropriately placed, and I actually enjoyed it. That is hard for me to believe. I now have a newfound hope that one day I may have a love for Bollywood films in the same way I love American independent, Japanese, and Swedish movies.

The disclaimer in the beginning of the movie Mangal Pandey: The Rising suggests to the audience that its portrayal of history should be taken metaphorically as social commentary instead of literally as established “facts.” Lois Krieger, the author of “History written with lightning,” argues that “film can show history as it was,” bringing the past to life in moving images in a way that serious written work cannot.

The disclaimer in the beginning of the movie Mangal Pandey: The Rising suggests to the audience that its portrayal of history should be taken metaphorically as social commentary instead of literally as established “facts.” Lois Krieger, the author of “History written with lightning,” argues that “film can show history as it was,” bringing the past to life in moving images in a way that serious written work cannot.